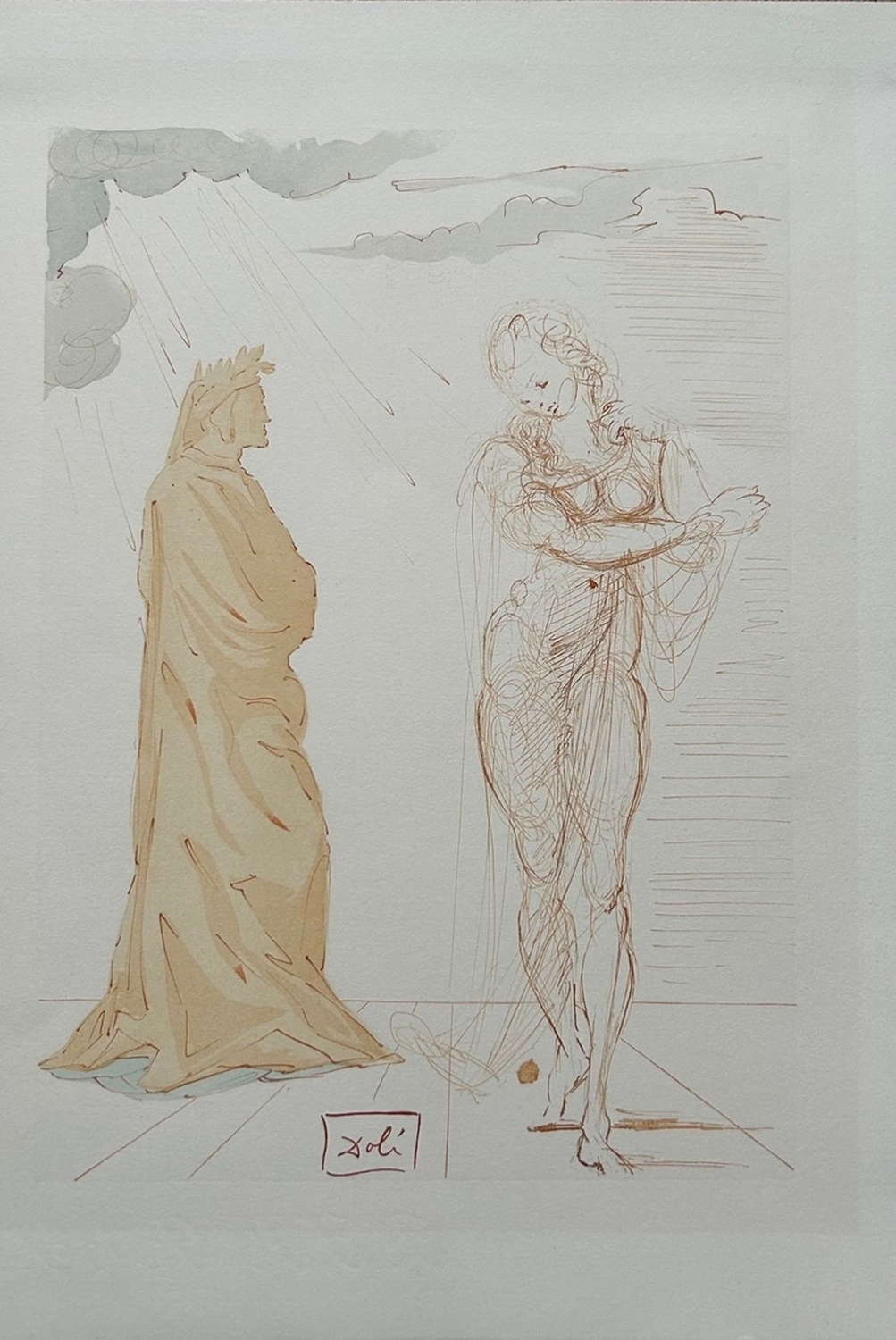

Salvador Dali's Plate Signed Woodblock Print 1963

Code: 12610

Dimensions:

Salvador Dali's Plate Signed Woodblock Print entitled Virgil Comforts Dante from the Inferno Series 1963

This woodblock print entitled Virgil Comforts Dante is from the Inferno Series of the now-very rare German Edition of 1000 with the the prints bearing Dali's characteristic signature

Dimensions: Sheet size: 33 cm x 22 cm and Image size: 28 cm x 18 cm

Condition: Near Fine

Note on Dante’s Divine Comedy Suite

The Divine Comedy (Italian Le Divine Commedia) the long narrative poem, written in Italian circa 1308-21 by Dante Alighieri (Dante) is generally regarded as one of the world’s great works of literature. (Its original name was La Commedia). It is divided into three major sections – Inferno, Purgatory and Paradiso.

The poem traces the journey of Dante from darkness and error to the revelation of thedivine light, culminating in the Beatific Vision of God.

Dante is guided by the Roman poet Virgil, who represents the epitome of human knowledge, from the dark wood through the descending circles of the pit of Hell (Inferno).

Passing Lucifer at the pit’s bottom, at the dead centre of the world, Dante and Virgil emerge on the beach of the island mountain of Purgatory. At the summit of Purgatory, where repentant sinners are purged of their sins, Virgil departs, having led Dante, as far as human knowledge is able, to the threshold of Paradise. There Dante is met by Beatrice, embodying the knowledge of divine mysteries bestowed by Grace, who leads him through the successive ascending levels of heaven to the Empyrean, where he is allowed to glimpse, for a moment, the glory of God.

Between 1951 and 1960, Dali had painted 100 watercolours, creating 34 watercolours illustrating Inferno, 33 illustrating Purgatory, and 33 illustrating Paradise.in preparation for the publication of “The Divine Comedy.” These watercolours explored the many myths and elements of this magnificent work of literature by the great Dante Alighieri.

On 19 May 1960, an exhibition of the 100 watercolours illustrating the 14,000 verses of Dante Alighieri’s “The Divine Comedy” was presented, with Dali in attendance, by Joseph Forêt and Les Heures Claires at the Museum Galliera in Paris.

Dante envisaged Hell in nine circles, with steps descending to the very depths of the earth. On this journey to Hell, they find the damned in a series of terraced levels where they are punished according to how bad and perverse their sins are. They all suffer terrible torments in scenes of terror, violence, and the presence of monstrous creatures. And worst of all, that is where they must remain for all of eternity.

It is in the watercolours illustrating “The Divine Comedy” that the genius of Dali was so overwhelmingly evident. For Dali, it was instinctual for his creativity and talent to be completely unrestricted through is surreal imagination.

Nowhere is it more evident than in the visual power of these watercolours by Dali, offering levels into Dante’s “Divine Comedy” that could never before be reached by words alone. In many respects, Dali felt himself to be Dante. As Dante’s interpreter, Dali felt obligated to follow the verses of “The Divine Comedy” and, through his watercolours, not only explain but also reconcile the writing of Dante.

By attempting to take the viewer pictorially through Dante’s series of incredibly complex situations, he set himself a difficult task, one almost impossible to achieve.

Being Dali, it was impossible for him to refrain from applying his own interpretations – free and new. His fantasy took flight and gave free rein to explore his own symbols and ghosts, so that, on many occasions, in the view of some commentators, unforgivably went off the track of the images as Dante described them in the text.

The suite contains complex and bewilderingly striking imagery ranging from the grotesque to the sublime, as Dali follows Dante from the deepest circles of Inferno, up the mountain of Purgatory, and into heavenly Paradise.

The illustrations of “The Divine Comedy” are considered by many to be the most creative total body of work ever by Dali. Dali himself thought this suite to be one of the most important of his career and it is

considered by many today to be his most incredible and notable work.

The illustrations represent the long journey that Dante took in 1300. In “The Divine Comedy,” it was on a Good Friday that he became lost in a dark wood and is attacked by three beasts: a panther, a lion and a she-wolf.

His platonic love for Beatrice sends [the Roman poet] Virgil to protect and guide Dante through the beyond – a trip through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise which Dante was to name “The Divine Comedy.”

Dali’s 100 watercolour drawings interpreting the Divine Comedy were reproduced using a wood engraving technique. With this technique, wood engravers carved 3,500 woodblocks for the prints that make up the book, approximately 35 separate blocks per image.

Each woodblock from Salvador Dali Divine Comedy is part of a Canto or book chapter. A Canto is about 8 pages long.

Working in conjunction with Salvador Dali, Raymond Jacquet, with his assistant Jean Taricco, created the blocks necessary for the engraving process. While frequently referred to as “wood” blocks, they were actually a resin-based matrix.

Salvador Dali directly supervised the production of the works and gave final approval for each of the finished engravings.

Once the project was complete, all of the Divine Comedy blocks were destroyed. The engraving process required the block be cut, a single colour applied, then printed to the substrate such as paper on silk. The block was then cleaned and cut away for the next colour.

As the engravings were made, the image was progressively “printed,” and the block was progressively destroyed. The process required great skill and resulted in works of spectacular beauty produced in a manner that is not detectable as a reproduction, even by an untrained eye.

In ‘Dali – Illustrator’, Eduard Fornes discusses the long and difficult work that was required to transform Dali’s 100 watercolours into a series of engravings which Fornes argues ‘can comfortably and properly be referred to as spectacular.’

The engravings produced 100 woodblocks in the French edition. Two different editors published the French edition. There are 4,765 books in French and 3,188 in Italian. Later, in 1974, a German edition with a stated size of 1,000 was also published. The German edition is different in that the set contains no text, just the woodblock prints ‘signed Dali’ Our Comment

Dali’s illustrations highlight the artist’s distinctive Surrealist interpretations of each of the three sections of Dante’s epic poem, ‘Hell, Purgatory and Paradise’, and demonstrate how his iconoclastic creative genius was deployed to create images that interact with the text of the great Florentine poet.

Note on Salvador Dali (1904 – 1989)

Salvador Dali known the world over for his flamboyant and multi-dimensional Surrealist style was a Spanish artist born on 11 th May 1904 in the town of Figueres in Catalonia to Salvador Dali Cusi, a middle-class lawyer and notary, an anti-clerical atheist and Catalan federalist and Felipe Domenech Ferres, who encouraged her son’s artistic endeavours from an early age.

Renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, strikingly bizarre creations, overt eroticism, graphic and symbolic sexual imagery, psychological allusions and other worldly colours in his work, Dali is widely considered as one of the most captivating, iconoclastic and prolific artists of the 20 th century.

He was equally well known for his eccentric and ostentatious behaviour throughout is life.

After World War II, Dali, became one of the most recognised artists in the world and his long cape, walking-stick, haughty demeanour, and waxed upturned moustache became iconic symbols of his brand.

His classical influences included Raphael, Bronzino, Francisco de Zubaran, Vermeer and Velasquez. Critics noted an apparent inconsistency in his work by the use of both traditional and modern techniques and motifs between works and within works.

As he developed his own style over the next few years, Dali made some works strongly influenced by Picasso and Miro. He also borrowed heavily from the work of Yves Tanguy.

Dali lived in France throughout the Spanish Civil War years (1936 to 1939) before leaving for the United States in 1940 where he achieved commercial success. He returned to Spain in 1948 he announced his return to the Catholic faith and developed what he called his ‘nuclear mysticism style’, based on his interest in classicism, mysticism, and recent scientific developments.

Heavily reliant on the psychoanalytic writings and theories of Sigmund Freud, throughout his long artistic career, Dali explored symbolic dreams, the subconscious, sexuality, fetishes, religion, science, closest personal relationships and autobiographical imagery in his paintings, graphic art, sculptures, artefacts and mixed media work. He extended his prodigious talent, prolific artistic imagination and skills to fashion design, jewellery design, sets for theatre and photography, at times in collaboration with other artists and film makers like Luis Bunuel and Alfred Hitchcock.

Deploying a symbolic language of his own invention, that included melting clocks, bureau drawers and bizarre animals, Dali investigated the tormented landscape of his own subconscious drawing upon Dadaism, Cubism and political writings.

Dali’s best known work, The Persistence of Memory (1931), which depicts melting clocks in a desert-like dreamscape of abstract Surrealism is one of the most famous Surrealist paintings.

The general interpretation of the work is that the soft watches are a rejection of the assumption that time is rigid or deterministic. This idea is supported by other images in the work, such as the wide expanding landscape, and other limp watches depicted being devoured by ants.

From 1927, Dali’s work became increasingly influenced by Surrealism. Two of these works Honey is Sweeter than Blood (1927) and Gadget and Hand (1929) were show at the annual Autumn Salon in Barcelona in October 1927. Dali described the earlier work, as ‘equidistant between Cubism and Surrealism’. The works generated amusement among the public and debate among critics about whether Dali had become a Surrealist.

His boastful public proclamations of his genius became essential elements of Dail’s public persona, the most well-known of which was: ‘Every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dali’.

In 1941 the Director of Exhibitions and Publications at MoMA wrote: ‘The fame of Salvador Dali has been an issue of particular controversy for more than a decade.......Dali’s conduct may have been undignified, but the greater part of his art is a matter of dead earnest.’

When in 1979, Dali was elected to the French Academy of Fine Arts, one of his fellow academicians stated that he hoped Dali would abandon his ‘clowneries’.

Dali died in 1989 at his beloved Teatro-Museum in Figueres, Spain.